Precise wavelength control is one of the most critical and most underappreciated challenges in laser diode and laser applications. Whether you are pumping a Yb-doped fiber laser, driving a solid-state crystal, performing Raman spectroscopy or locking an atomic transition line like Rubidium at 780.24 nm, your experimental success depends not just on having a laser diode, but on having one that emits at exactly the right wavelength.

The problem is that manufacturing a laser diode is nothing like machining a screw. Semiconductor fabrication tolerances are wide by nature. A standard off-the-shelf laser diode datasheet typically lists a center wavelength tolerance of ±3 nm and in some cases as wide as ±15 nm. If your application demands 976.0 nm or 808.0 nm precisely, but the laser diode you received from the supplier emits at 970 nm or 807.5 nm, does that make it useless? Not at all. This is where laser diode temperature tuning becomes the engineer’s most powerful tool turning an out-of-spec component into a precision light source without replacing a single part.

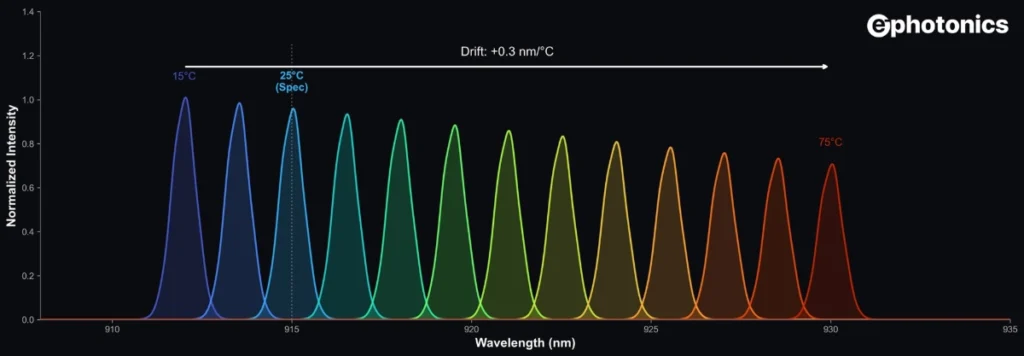

Laser diodes differ fundamentally from gas lasers in how their emission wavelength is determined. In a gas laser, photons are emitted at fixed atomic transition energies, the wavelength is essentially locked by nature. In a laser diode, however, the emitted wavelength is tied to the semiconductor material’s bandgap energy. As temperature rises, this bandgap narrows, meaning electrons and holes recombine at slightly lower energy levels and emit longer-wavelength photons. The result is a predictable redshift and for most InGaAs laser diodes, this amounts to roughly 0.2–0.3 nm per degree Celsius.

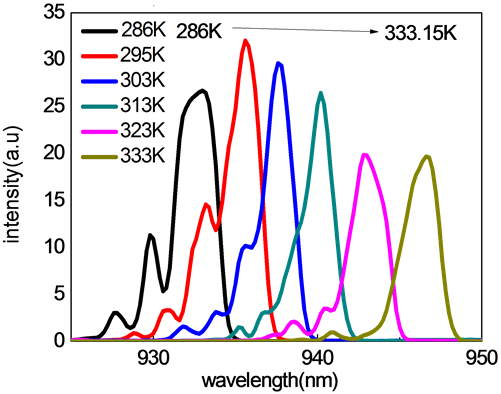

The figure below shows this effect directly, showing a 940 nm InGaAs laser diode’s central wavelength climbing from 930 nm to 945 nm across a temperature sweep, a shift large enough to ruin a narrowband application.

What makes this especially useful in practice is that the shift is highly repeatable and monotonic. Unlike mechanical tuning methods, there is no hysteresis, no moving parts, and no risk of misalignment. Once you characterize your specific laser diode’s tuning curve, typically by measuring wavelength at several stabilized temperatures, you have a reliable map that lets you dial in your target wavelength by simply setting a temperature setpoint on your TEC (thermoelectric cooler) controller.

Many engineers are surprised to discover that a laser diode sitting 5–6 nm away from their target wavelength at room temperature can be brought precisely on-spec with nothing more than a temperature adjustment of 15–25°C.It is worth noting, however, that temperature tuning has limits. The tuning range of a Fabry-Perot laser diode is relatively broad and continuous, but a DFB (Distributed Feedback) laser diode, which uses a built-in grating to enforce single-mode emission has a narrower tuning window, typically 1–3 nm over its full operating temperature range. Choosing the right laser diode architecture for your application therefore matters before you even think about tuning.

To understand why temperature moves the wavelength of a laser diode, you need to look at two things: the semiconductor bandgap and, depending on the laser architecture, the optical cavity. In any semiconductor, the bandgap, the energy difference between the valence band and the conduction band which determines the minimum photon energy the material can emit. When an electron drops from the conduction band to recombine with a hole in the valence band, it releases energy as a photon.

The wavelength of that photon is directly tied to this energy gap through the relation λ = hc/E, where h is Planck’s constant, c is the speed of light, and E is the bandgap energy. As temperature increases, the crystal lattice expands and atomic vibrations (phonons) intensify, which weakens the periodic potential holding electrons in place. The bandgap shrinks. Smaller bandgap means lower photon energy, which means longer wavelength, namely redshift.

This relationship is quantified by the Varshni equation, first described in a 1967 paper on the temperature dependence of semiconductor bandgaps, and remains the standard model used in photonics engineering today [2].

where Eg(0) is the bandgap at absolute zero, and α and β are material-specific fitting parameters. For InGaAs, the material family behind most 900–1000 nm pump laser diodes, this translates to an experimentally observed tuning coefficient of approximately 0.27–0.32 nm/°C.

For Fabry-Perot (FP) laser diodes, a second effect compounds this: the refractive index of the gain medium also increases with temperature, which lengthens the effective optical path of the cavity and shifts the resonant modes to longer wavelengths. Both effects push in the same direction, giving FP diodes a relatively wide and continuous tuning range.

For DFB laser diodes, the wavelength is instead pinned by a fixed-period Bragg grating etched into the waveguide. Here the dominant tuning mechanism is the temperature dependence of the refractive index, not the bandgap directly. This makes DFB tuning slower and narrower, typically 0.08–0.12 nm/°C, but far more controlled and mode-hop free, which is why DFBs are the preferred choice for applications like atomic spectroscopy or LIDAR where a single, stable longitudinal mode is non-negotiable.

Understanding which mechanism dominates in your laser diode is not just academic. It tells you how much tuning range you have, how linear that tuning will be, and whether you risk a mode hop, a sudden discontinuous jump in wavelength, if you push the temperature too far.

Not all laser diodes tune at the same rate. The tuning coefficient, how many nanometers the emission wavelength shifts per degree Celsius, varies significantly depending on the laser diode architecture and the underlying physics driving the shift. Fabry-Perot emitters, where both bandgap narrowing and cavity expansion contribute, shift faster and over a wider range. DFB and DBR laser diodes, where the wavelength is locked to a grating, shift more slowly but with greater stability and mode purity.

VCSELs sit at the slower end of the spectrum due to their very short cavity length. The table below summarizes typical tuning coefficients across the most common laser diode types to help you quickly assess how much temperature control range your application will require. Tuning coefficients vary by material composition and can be cross-referenced against NIST material property databases for your specific epitaxial structure.

| Laser Diode Type | Typical Wavelength | Coefficient (Δλ / ΔT) |

Dominant Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| FP Single Emitter (InGaAs) | 900 – 1100 nm | 0.27 – 0.35 nm/°C | Bandgap + Cavity |

| FP Single Emitter (AlGaAs) | 780 – 870 nm | 0.20 – 0.30 nm/°C | Bandgap + Cavity |

| FP Broad Area (InGaAs) | 900 – 1000 nm | 0.28 – 0.33 nm/°C | Bandgap + Cavity |

| DFB Laser Diode | 760 – 1600 nm | 0.08 – 0.12 nm/°C | Refractive Index |

| DBR Laser Diode | 760 – 1100 nm | 0.06 – 0.10 nm/°C | Refractive Index |

| VCSEL | 650 – 1550 nm | 0.05 – 0.08 nm/°C | Cavity Length |

Explore our catalog of fiber-coupled high-power wavelength-stabilized laser diodes engineered for high-performance.

Explore Laser Diodes

While our laser diode tuning calculatorhelps you predict and compensate for wavelength shift, maintaining that perfect setpoint in a real-world environment is a different challenge entirely. Fighting thermodynamics/wavelength with a TEC controller works well in a controlled lab but it can become expensive and complex when your ambient environment fluctuates, your system needs to be compact, or your application simply cannot tolerate any residual drift.

If your use case, Raman spectroscopy, precision optical pumping, or atomic line locking demands absolute wavelength stability regardless of thermal conditions, mathematical prediction alone is not enough. This is where a Wavelength Stabilized Laser Diodes with VBG becomes the right engineering choice. By integrating a Volume Bragg Grating (VBG) directly into the package, the emission wavelength is physically locked at the grating period rather than floating with the semiconductor bandgap. The result is a dramatic reduction in temperature sensitivity from ~0.3 nm/°C in a standard FP diode down to just 0.01 nm/°C, effectively eliminating the need for aggressive active temperature tuning.

ephotonics offers a premium range of laser diodes, available across multiple center wavelengths and output power levels. Engineered for applications where being close is not close enough, these modules stay locked on your target wavelength regardless of thermal stress or operating conditions.

References

[1] Y. Liao. et al., (2016) “An Experimental Study on the Temperature Characteristic of a 940 nm Semiconductor Laser Diode“, Optics and Photonics Journal, 6, 75-82.

Join our newsletter to stay updated with new articles and news!

ephotonics is a go-to partner for photonics solutions, with deep expertise in laser electronics and laser design. We’re committed to delivering effective solutions for laser-based applications and sharing helpful articles. To learn more about us, check out our About page.